A husband finds his wife’s diaries after her death. Transported through time, he discovers a side of her he never truly knew. A timeless story of love, loss and life.

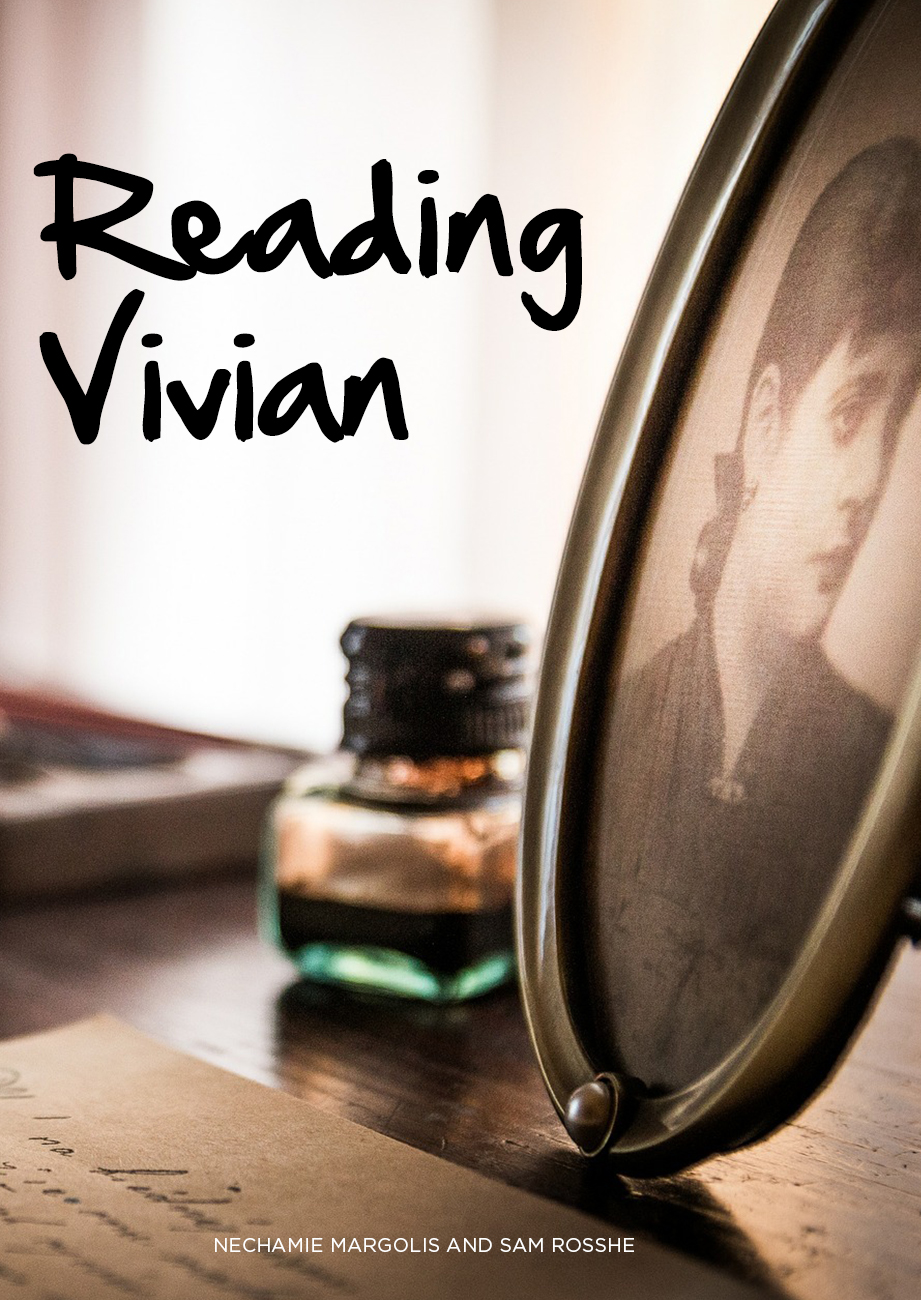

Reading Vivian

All That We Lost and Found

February 28, 2016

Reading Vivian

Nechamie Margolis and Sam Rosshe

He called her a three Dumpster person. The name wasn’t so nice, he thought, but it was apt, and it made so much sense. He was standing between walls unpainted for twenty-five years, because there was no way to move the sheer volume of stuff, heaping mounds of unused textbooks, dust-covered Pisa towers of outdated computer programs, hills of broken cameras, stacks of ancient yearbooks.

His Aviva. To everyone else she was Vivian, but he claimed her second name as his own. She was gone.

And now the things she left behind. So many of them.

He started the day after shiva, the mourning period, was over.

Called a truck to remove dresses, jackets, skirts crammed into her closets.

“Abba, it’s too soon,” the children pleaded. “Please wait.”

Nathan’s eyes sunken with loneliness that suddenly leaped on him, the salt-and-pepper growth on his chin that he stopped shaving, a visible, throbbing reminder of his loss.

No. He’d had enough. He didn’t need her things in order to grieve.

“I gave away a dress once,” he said. “Just one dress. A dress that she didn’t wear in ten years. She never forgot it. For thirty years, she never let me forget I gave away her Prada dress. I’m choking from the stuff. Take what you want. The rest has to go.”

He tackled the pantry next, crammed with boxes and packages and cans of food. Threw away, gave away.

The Dumpster was overflowing. Heaps of textbooks going thirty years back, from the days when she taught math, more broken cameras . . .

And then it was time for the office.

For thirty years, he didn’t cross the threshold, an unspoken, non-negotiable demarcation line.

“My shalom bayis room,” she told him then. “My world. I want to keep it mine.”

Now, he trespassed on the holy of holies, as it lay deserted.

Thirty-seven notebooks filled with notes on Torah classes she attended over the years, vast collection of cookbooks, piles of decorating magazines, troves of brochures hugging the wall for balance, files with recipes and correspondence and receipts on every party she hosted, menus from every restaurant they visited.

This cavernous chamber of little moments of life covered with dust and abandonment assaulted him with grim solemnity of frozen joy left behind. For a moment, he had the urge to sink on the floor in despair. But no space anyway. He chose what he would always choose. A man of action, he rallied. He was here for a purpose, he reminded himself. To find the diary. If there was one, there must be more.

Opening and closing drawers, knocking over precariously balancing piles with uncharacteristic clumsiness, he finally got hold of his trophy. Two small worn pocket-size diaries.

Quietly, he closed the door behind him, as if not to startle the shadows lingering in the corners of a desecrated space, and escaped to his office.

Held the diary for a moment. Ran his finger over the dusty cover. Young Vivian, from the days he first met her, lived inside those pages, frozen in time.

Two days before she died, she sent her daughter, Shira, to get something from her office. Instead, Shira came back with a small book. “What’s this, Mommy?”

“It’s for Daddy. Give it to him, please.” Agonizing pain, a tumor pressing against her spine, made her words a staccato beat.

The night before Vivian died, Shira handed the small book to Nathan. He stuffed it into his drawer. Too much was going on to give it a thought.

Later, poring through the pages he would stumble upon these lines:

It happened so fast, so many memories that I would like to hold on to. I hope I do hold on to them, for some seem to be fading. Nathan, the one person in the world that I shared my life with, has forgotten a lot of our past. I guess he put me “in charge” of the remembering . . .

It would make him scoff. Again this cliché, women remembering everything that men forget. Many pages later, her painstaking act of remembering would grow on him, but not yet. As the life itself, it would have to run its course.

And then he was packing for the plane trip to Israel to escort Vivian on her final journey. He opened the drawer to look for his passport and saw the book. Stuffed it into his carry-on bag.

He opened it when the plane took off. A handwriting he knew so well.

December 6, 1958

Dear Diary,

Today, Hanukkah, I was so surprised when I received this book. Mommy hid all the presents and wouldn’t tell us what they were. I was expecting a present but didn’t think it would be a diary. I’m awfully glad it was.

Your dear, dear, dear friend Vivian

He didn’t need to do the math. Vivian would have been in seventh grade. Her first year in Hebrew Day School in Lincolnwood, Illinois, and his seventh.

For the eleven hours that it took for a plane to touch down in Ben Gurion Airport, he read. His heart aching, he drank her every word. Like in the old days, she was talking to him with that tantalizing voice of a teenager, a beautiful initiate into her first years of womanhood.

Vivian goes to junior high now. It’s all so important, as important as it can be for an adolescent girl in love with her life. She is happy she changed schools. She cherishes her newly found popularity, proud of her good grades. She shares with the diary her secret craving for dresses and coats that can be taken off the racks, measured, wrapped up, and bought in clothing stores, instead of the hand-tailored clothes her Italian-born mother sewed for her.

Nathan chuckled when Vivian wrote to her diary, in horror, that she found out her mother was sewing tags to her clothes so that they would look like they were bought at a department store.

Her deep love for her grandmother who came to live with her parents in their small apartment. It was so small that Vivian had to share a bed with her. For Vivian, it turned out to be transformational. She absorbed her grandmother’s deep faith in God, learned to read the shema every night, every single word of it. The wise heart of an old woman who has lived her life, and a naive heart of a girl who was only beginning hers, reciting together the immortal credo of the living.

The plane tilted to a side, drawing a wide semicircle high above the Mediterranean, heading straight to the shores of Israel, bringing him closer and closer to the finality of her death. Each page he read, resurrected a Vivian he never knew.

9th-grade basketball team in my life. What fun! Practiced every night and got really good.

That hadn’t changed. She was famous for her two-handed set shot. Then her tennis games she played every week for thirty years until her eyesight and knee gave way.

Boys frequented my driveway to play—terrified of my father who shooed them away, but they bravely came back.

Opened a school book and found a note written by a classmate. He writes he’d love to take out Vivian but afraid of her father.

My house is on Regina Lane in the center of town. Girls make plans before Shabbat, they say meet you at Vivian’s. But they never ask me! Instead of reading a book as planned, I have to entertain. But not so bad because my father doesn’t let me go out much unsupervised and this way I socialize. Mom bakes lots of goodies.

The plane taxied to the gate. He closed the diary. He will be back, to his young Vivian. Now he had to bring her to a burial. After the formal funeral back home in Lincolnwood, two hundred people would come to bid her final farewell in Israel.

She always loved Israel with passion, asked Nathan if he would consider moving when they first visited there on their honeymoon. A dream come true when they came to Israel on an impromptu sabbatical in 1988. They gave it a shot. He immersed himself in learning, and Vivian did her best to help them make it work in Israel, in their apartment in Rehavia, hosting a full house of guests every Shabbos. She knew they had to go back, but there was always a place in her heart where Israel remained a part of her soul, and she remained a part of Israel.

She was happy when they bought a modest house in a quaint hilly Jerusalem neighborhood. She so much wanted Jerusalem to be their home. “I have two lives,” she would say. “One life here and one life there.” Both were so meaningful to her, but Israel spoke to her soul. Now she returned, and the people she knew from decades back, remembered her. They came, too.

. . .

And he is back in their empty house, huddling in his office with two more diaries that were about to tell him the tale of the Vivian he lost. Five years of her life.

He held the small book closer to his eyes—the crowded script leaping across pages, page after page, strained his eyes.

April 1964. They were in the same class, but he watched her for a long time already, keeping a safe distance. Then their paths met. He was the yearbook editor in chief, she the photography editor. He knew how to tell everyone what to do. She actually had a skill. She knew how to measure focal lengths, set light flashes, and develop film.

He claimed he was smitten when she came to him with the yearbook pictures. She claimed he insulted her and resented having a woman on staff. Not a great start.

That changed on a school field trip to World’s Fair. Barry, their classmate, asked to sit next to her on the train, and then they roamed the fair together. But then, Nathan stepped in and persuaded her to accompany him.

April 30,1964

Whereas Barry is sincere and nice; Nathan is more fun. Actually, it wasn’t all my fault; Nathan was pretty possessive.

Possessive. What a word! The diary remembers everything. A workaholic, working eighteen hours a day, nights and weekends, he used to be fun once. Why couldn’t he stay this way, for her? Where did he lose it? Maybe this word possessive—with a sandpaper quality to it—is the clue, he thought.

He was a guy who was in hot pursuit of success. Naively, he thought it stood for pursuit of happiness. Looking back, he knew it didn’t. As much as he was possessive, he was possessed, and wasn’t free enough. Free to feel, free to be.

There are 450 days from April 30, 1964 until July 1, 1965, and 450 daily entries. Nathan is in 390 of them.

May 19, 1964

Nathan called at night. I have a lot of fun talking to him.

June 2, 1964

Nathan said he used to look forward to no school but now looks forward to school. What a nut! (But a nice nut!)

June 7, 1964

Nathan played accordion. I explained I did not want to get serious. He’s a character. I hope he doesn’t get hurt but I warned him that one of us probably would.

Nathan smiled. That was fun, strapping his accordion and serenading her. Talking to her, patiently, month in and month out—and sometimes not so patiently—about her doubts. Writing a letter to her parents, politely explaining his desire to continue dating their daughter.

Son of two generations of lawyers, his language was eloquent, convincing, artful, accentuating all the commas and full stops, dashing forward, making his case in front of a jury. He humbly acknowledged their concern that he was coming from a nonreligious family, but politely assured them of his solemn commitment to Judaism. He was a man of his word. He kept his commitment.

. . .

Page after page, entry after entry. Gradually, he was growing into the tapestry of her thoughts, of her dilemmas, of her fantasies.

October 4, 1964

I’m flattered by the way he talks to me but I’m hurting him. I don’t feel strongly enough to reciprocate.

October 27, 1964

Told him I’m not used to giving up all of my time for one person,

December 3, 1964

We almost broke it all up—I was sarcastic. He wants more from me—I want less from him. I wonder how it will all end or if it will.

December 9, 1964

Felt very close to him today.

December 13, 1964

He is such a gentleman.

December 14, 1964

I felt just plain happy liking Nathan and finally really feeling it. Debra actually sensed that I could conceivably marry him.

December 26, 1964

4 hours on the phone.

December 31, 1964

5 hours on the phone.

February 22, 1965

Discussed with Mom how mixed up I was. It is hard because she does not want him.

A lot of laughs, fun, and crying. Possessive and persuasive. Can’t go out with others under his watchful eye. He gets hurt if I even say I want to try and date someone else.

Nathan stopped reading. Felt a slight flush of embarrassment seeing himself through her sarcastic eyes. Possessive and persuasive, a tandem of words annotating her thoughts of him. He was always proud of the way he pursued her. He was determined, dedicated, single-minded. A key to his business success.

. . .

A memory. He and Vivian playing tennis against another couple. She missed shots one after another, and he got agitated.

“It’s not all about winning,” she defended herself.

“Yes, it is!” he retorted.

“So play by yourself.” She walked off the court.

. . .

Winning Vivian. He had won. But maybe it wasn’t about the winning after all. Maybe it was about playing the game of life. Hard to know now, when the first prize was snatched from his hands . . .

She kept reminding him of the chronology of his victory:

June 9, 1964

Nathan gave me typewritten courtroom scene. What a riot! Very clever!

June 15, 1964

Nathan dropped off a 3-page play about us.

June 24, 1964

We played tennis; he bossed me around, ordered me to chase the balls, and tired me out, but possibly taught me something.

June 25, 1964

Prom night. I was in a sort of wild mood—laughing and singing.

July 2, 1964

Nathan and I played water volleyball. He’s a riot.

July 3, 1964

Sat with Nathan on the beach and talked serious.

July 13, 1964

He said he needed me! Don’t know what to do!

August 22,1964

Stopped to talk and discuss his letter. Pretty sentimental one—wants to bring a present each time he comes.

September 8, 1964, Rosh Hashanah

We walked to the beach. He said he loved me and would marry me tomorrow if he could. I got tears in my eyes. He’s a doll, but . . .

He remembered how she saw the trees in the snow, passersby, children wrapped in colorful scarves riding their sleds down the slope, their laughter sparkling like icicles in cold sun. He was a man on a mission, with only one goal in mind. She was too distracted by the inconsequential beauty of the present moment, while he needed to close the deal. Was she ready to close the deal? “Wait,” she told him, “I’m not ready yet for the questions that cannot be taken back.” He remembered that crushing feeling inside him, but he wasn’t going away.

September 10, 1964

I like him . . . I think.

January 30, 1965

“Could be love . . .”

April 8, 1965

Talked total of 3½ hours. We don’t get tired of each other.

May 20, 1965

Am so happy. Nathan made very elaborate birthday plans. The best birthday I ever had except for when I was born.

June 28, 1965

I wonder if I am doing right. Mom doesn’t seem to think so.

By now, forty-seven years and one funeral later, he knew he was telling the truth back then on the beach. And now this vast ocean between them, but he still loved her, his Aviva, lying so far away, alone, and he was alone, too. Back then, she was ambivalent if his truth was her truth as well, but all he knew was that he had to convince her. He was blindsided by his persuasive self. Only now he realized that this was exactly what made her ambivalent.

It hurt.

. . .

Staring at dense script for hours, his eyes felt hot and heavy. The words merged together. He leaned back, closed his eyes. Life played across the screen of memory. Those precious moments that survive time, illness, failures to be who we wanted to be.

Moments that survive death.

Vivian, a beautiful young girl, in the phone booth outside of Touro College. She smoothed back a flyaway strand of hair. A phone rang on the dot. She didn’t want to appear anxious, let it ring. Two times, three times. On the fourth ring, she picked up.

“Aviva.” His voice was deep, resonant. He was the only one who called her that. “Aviva, how are you?”

They chatted for a minute or two.

“Can you hold for a moment?” Nathan said suddenly.

Vivian held the phone in her hand, slightly annoyed. Why was he making her wait? It’s not a way to treat a girl. He never did this to her.

A knock on her phone booth startled her. This was her territory for the moment, a glass cubicle filled with dreams, doubts, and youthful fantasies.

She poked her head out.

“Oh, Nathan,” she laughed. “You startled me!”

“Well, well,” he said, taking the phone and placing it back in the cradle. “Since I’m here anyway, why don’t we go for a little walk. . . .”

. . .

Still immersed in memory, Nathan leaned back in the armchair, took off his reading glasses. He almost felt her presence, as if she were looking at him with her slightly sad smiling eyes, speaking to him without words.

“I have my doubts,” her eyes were telling him . . . “You’re so serious. Cynical sometimes. But then out of the shadows comes this other side of you, with five-foot birthday cards, or you remember that little prank with a miniature model of a Mustang you gave me, and we were going around telling people that you bought me a Mustang. I know life will always be interesting with you.”

And it was. He loved to surprise her. Jewelry on random occasion, surprise vacations, flying in their son from Israel for Hanukkah, little things that made her happy. And when she was so sick, the final surprise of them all, the last one he had a chance to present her with.

“We need to interview a new aide,” he told her. A minute later, her cousin from Italy walked in the door. She needed to say good-bye, and he gave her that.

Anything to bring that light of joy into Vivian’s eyes even if it hurt like hell.

. . .

And then, an entry that made him pause.

My aunt Daniella said, If he wants you that much, he’ll make a great husband.

But now he wondered. Is it always true? When we want something so much, does it make us so unbelievably great? Or all it means is that we are tenacious, for better or for worse? Was it for worse? He almost panicked. He was desperately searching for clues between the lines. Suddenly, he realized, it was a question of his life.

He always prided himself for being a rational man, and now he found himself having an almost frantic dialogue with a diary. Yes, now he remembered what he had forgotten. He is facing a question that he has to answer. He feared this question his entire life. Now the time has come to face it. Now or never. Whatever the answer will be.

. . .

He brings her to the Hebrew Day School basketball court, the place where their courtship began. Gets down on one knee. “Will you marry me?”

Even as she mouths the word he has been anxiously waiting to hear for two and half years, he knows the answer. He was good at reading other people’s intentions. He knew the answer the day she sent him the card. She signed it “from a sentimental friend” and added, in parentheses, “who is not even mixed up anymore—no doubt about it!” This was a hint, and she deliberately planted it there! She wasn’t uncertain! He knew that she knew. That day, he was like a moonwalker, a foolishly sentimental one, stumbling into furniture and smiling, and no one knew why. But he did, and she did.

. . .

Of all the boys who chased Vivian, who wanted her irresistible charm, her joie de vivre and her good looks all for themselves, he was the one who placed a diamond-studded watch on her wrist as a seal and testimony of her saying yes. She gave her heart to him, to Nathan. He scored his huge win. He didn’t even know then how huge.

They got married in front of the Hebrew Day School they’d attended. Nathan wrote to the transportation department requesting that the planes that flew overhead be temporarily rerouted for the half hour of his chuppah. To everyone’s astonishment, he got a response: Yes, they wish him and his future wife all the best and will do all in their power to accommodate his request.

That night, they stood under the stars, Nathan and Vivian. Perfect silence for a brief moment. It worked, Nathan gloated. Then the skies exploded in a deafening roar as plane after plane on a descent flew overhead, as if on a bombing run. The voice of the rabbi was drowned out. “You called for an aerial support?” he whispered to Nathan.

. . .

The life geared up on its runway. Starting from ground zero, they couldn’t afford a rental. They moved in temporarily with Vivian’s parents.

Rabbinical ordination studies during the day, law school at night. Being a super achiever, he loved flexing his willpower, his intellectual muscle. He loved hard work and he loved success. And hey, he loved Vivian, the prettiest girl of all, for whom he did all this.

But then he realized that he disliked practicing law, almost with the same passion as he loved Vivian and success. Then came the moment of truth when he confessed to her that he couldn’t do it anymore. He was quitting his father’s law firm and opening a business of his own.

She didn’t think it was a good idea. Back then, he should have listened to her, but he knew what he was doing, he always did. They bought a house. It was their dream house with a huge backyard, and they loved it.

But then the business suffered reverses. He remembered her eyes as he was making another confession. “Vivian,” he said, “we can’t pay the mortgage. We’ve got to sell.”

“No, no, no,” Vivian said. “We’ll do whatever it takes. And God will help.” Her faith was simple and real and deep.

Vivian did, just as she said, whatever it took. When she was sixteen, babysitting, she read the books in that emerging new and esoteric field called computer programming. She was fascinated and decided that this was what she will do, become a computer programmer, and she did. When she faced the dilemma of choosing between her children and her budding career, she chose her children, which even in her last days looking back, she never regretted. Now it came in handy. She taught math and computers to high school students. Sold computer programs. Gave private lessons on computer literacy from home. They kept the house. Her house.

Did he give himself the time back then to stop and think, to acknowledge her judgment, to admire her commitment, to revel in her hard work? He never denied it. He was always very proud of her. But he was too driven, too busy to remember. Now he was sitting in his armchair, flooded with all those memories he never had time for. They were waiting for him, and they came, sharing his loneliness. Her last gift to him.

He started a catalogue and showroom business selling supplies and displays to apparel retail chains. It grew and required a lot of traveling. He was busy, very busy, and Vivian found herself raising her four boys and daughter alone. “He’s a Shabbat dad,” she quipped, “and I’m a single mom the rest of the time.” A joke or a painful truth? A bitter complaint, or a sheer determination of a woman who decided to love life, whatever it threw her way?

“You only pass this way once,” his mother nagged him. “Spend more time with Vivian and the kids.”

But he had branches in San Francisco, Washington, Houston. He had to take care of them. And then the trips to the Far East to outsource the manufacturing, to cut the business expenses, to keep a competitive edge, to stay in the game and grow big.

One night, Nathan came back home and found Vivian brooding. “I’m leaving tomorrow,” he reminded her. “On a business trip.”

“I know,” she said, still looking distracted.

“What you’re thinking about?” he asked.

“Oh, nothing,” she said.

“OK,” he said, and returned to his dinner.

Didn’t he realize it was a cue? She couldn’t hold back.

“Just thinking,” she said. “Remembering when I went on the tour to Europe. You remember? I went to all those places, Lugano, Paris, London, Naples, and then Israel.”

Nathan laughed. “To get away from me!”

“Yes.” Vivian nodded. She looked serious, almost stern. “But you didn’t let that stop you. I was gone forty-nine days, and I got fifty-two letters, from you. They were following me across the continent.”

She still had those blue airmail letters. Nathan numbered each one of them, so that Vivian would know if one got lost in the mail.

“You can’t imagine how much I got teased, getting those letters every day. Then you came to the airport to meet me. I still remember that green shirt and beige pants you wore.”

“Your parents weren’t very happy to see me!”

“No, they weren’t. But I was. I was happy to know that you had me in your thoughts all the time.”

Vivian handed a white envelope to Nathan. “Write to me, please?” she said.

Nathan’s hand stayed where it was. “Write to you? What would I say?”

Deafening silence.

Nathan took the envelope. It was already stamped and self-addressed, waiting to go all the way back from China to Lincolnwood and tell Vivian that Nathan had her in his thoughts all the time.

She didn’t mention the letter when he came back. Was there a pang of remorse? If there was, he pushed it away. He loved her. She knew that. He proved it in so many other, much more real ways than writing that letter. Shouldn’t it be enough?

. . .

Nathan put the diary down. It was assaulting him. Words, words, words ringing in his ears, bouncing off the walls, making him listen to the room, so quiet this evening.

There was a letter on her bedside. He wrote it, finally, a few months before she died.

The letter was worn to a tear, folded and unfolded and read time after time, over and over again, as if it were written decades ago. Were those dried wet spots on the page?

The prettiest girl I ever saw was in the class of ’64” is a refrain I hum all the time. . . . I can’t contemplate losing you—I’d give up an arm or leg sooner. My love for you is unending, my admiration without limit. You are loved by all your peers because you emanate love. . . .

We have had a life replete with happiness because you created that milieu. All the kids carry that same badge—appreciated by all who know them as a reflection of their mother.

Nathan felt physical pain. What he would give now to write another letter, as many letters to keep her with him, to see the joy as her face lit up.

. . .

He was up before dawn. The diaries called him, shaking him from the fitful dreams in the midst of the great void, his life without Vivian.

But now there were the diaries. They were his call of duty.

He crossed the threshold again. Felt guilty, trespassing on this sacred space, her space. But then maybe Vivian was cheering him on, whispering to him, find me, hear me in the things I left behind, know me at last.

He pulled out the thick folder with the Yeshiva files. As so many times in life, it began almost by chance and grew to become perhaps the single most important thing they did together.

Vivian and Nathan went to Hebrew Day School, their alma mater, to register their first son. They roamed the school, reveling in memories of their youth. But they left without signing him up. There was a fledgling school in Lincolnwood they wanted to check out first.

The school was Yiddish-speaking, and the students were coming from a background much more strict religiously than theirs. But then Vivian heard the rebbe chanting the Aleph Bet with his students a capella. It sounded so ancient, so timeless, as if calling for their souls to take a journey of return.

“I want that,” Vivian said. “I want my children sing the Aleph Bet just like that. I want this to be their music.”

. . .

Having sent his child there, Nathan wanted the school Be’er Torah to do well. As much as he dedicated his acumen and drive to its success, the school reciprocated by giving him a greater purpose in life. He went on to work for the school, and Vivian became the PTA president. They helped bring in Rabbi Yekutiel Davidson as a principal, a brilliant choice. The student body grew two thousand strong.

Looking back, he was so happy they walked into that tiny fledgling school back then. Be’er Torah gave great education to his children, and Nathan was giving back with all the vigor and determination he could muster.

When Vivian lost her mother at the age of fifty-six, she was crying all the time. You don’t realize what you have until you lose it, she wrote.

“Get involved in the Yeshiva,” Nathan pleaded.

Vivian agreed. Shavuot, she ran the plant sale, storing hundreds of plants in her garage and back porch, watering and packaging them. Then the toy store before Hanukkah, with all proceeds to the Yeshiva. She went to the toy show in Chicago, studied ads and brochures, flew to New York once to buy closeouts. Then she launched an art and Judaica show, which transitioned into a silver show, for more than a decade.

The ads and brochures, the pages and pages of information, the receipts—all filed away, thick files speaking of years of devotion and creativity.

Nathan scanned the shelves for more. Medical records of her diabetes. Architectural plans for the houses they lived in. Checkbooks going back decades. Drawers full of business cards collected over the years. Thousands of pictures that didn’t make it into her photo collection, a total of 160 albums.

Thirty flashlights. Twenty-seven staplers. Slides going back to 1965.

He pulled down a thick book, filled with glossy pages of text and pictures. The Story of Us, it said.

He’d seen it before, occasionally flipped through the pages when she urged. Tried to show interest. But did he really take the time to read, to hear her voice?

The Story of Us. Shortly after her sixtieth birthday:

All that transpired in the last 40 years is so clear to me, I almost feel that I am still in that time period. Unfortunately, that clarity does not reside with your father since he has forgotten everything, claiming that he put me in charge of remembering. He has unbelievable clarity in all other matters though—be it business, law, finance, or learning that amazes me.

Nathan felt that he was hearing it for the first time. Gradually, the fog of the unspoken started dissipating, and the realization started dawning on him. He couldn’t articulate it yet, but it was there, the insight. What was it that stood between them, the invisible difference between his take on their life, and hers. She knew it all along, but he didn’t. Maybe he refused to know. Perhaps, he was too afraid to know. But now he has to. Painstakingly, reading her words, he was putting this together.

Back to The Story of Us:

I love pictures. I spent a whole day today going through all my pictures sorting and scanning. I wonder what will become of my precious pictures. Who will want them?

Pictures tell a story. They freeze time. They show how we once actually looked good. . . .

That night, he came home late. Vivian was sitting in front of the VCR player. “Please sit,” she said. “Let’s watch our wedding video.”

Her eyes sparkled, that love of life he wanted for himself, drew him to her. But at that moment, he was a coward. He shrugged out of his coat. “Too tired,” he said. “Another night, I guess.”

That night never came.

. . .

Then the night she sat with piles of albums.

“You have to see this picture,” she said. “Hard to believe how young we looked!”

“Have to go to a meeting.”

“Can’t you stay home just this one time?” Disappointment in her eyes.

“Yes, I must.” He ate dinner quickly and left. He almost ran for his life.

He ran from those pictures that made him so jealous that he felt sick to his stomach. He was jealous of himself. Jealous of that young good-looking boy who managed to capture the heart of the most beautiful and alluring girl in school. Both of them, so young and audacious and aware of the impression they were making as a couple. He missed the boy he was, being too busy chasing after the man he wanted to be.

He couldn’t look at those pictures.

Unarticulated words, hanging between them, were filling a whole world of Dumpsters. Nathan hiding behind work, and Vivian behind the pictures, the albums, the notebooks, the memories she wrote. She was fitting them inside a time capsule, a sprawling collection of things, many of them broken and superfluous, almost like the life itself, or so it felt at times. A repository for memories she couldn’t share with the one who owned them.

. . .

Nathan loved their home in Florida—empty of obligations and empty of collections.

And Vivian loved it as well, paradoxically for the same reason.

. . . the house is neat and clean without all the burdens of years of memories and pictures and things I collect. I can’t help it. I get attached to the memories and cannot rid myself of the pictures and “stuff.”

Even now Nathan could still feel the tension held in those piles of stuff, their creeping annexation from Vivian’s private life to every corner of the house. But he was starting to understand—the habit of collecting things was a metaphor.

She was trying to hold on to life—and on to him.

She was trying to hold on to their life that was passing like an express train. He was fleeing the very expendability of it, and now he was facing the nothingness.

The fear started creeping on him again, scraping at his entrails, breathing in his face the hollowness of a life without a past.

Nathan flipped through the memory book she spent hours and days and weeks creating. Mostly upbeat, but then, as she entered into her fifties, it gradually changed its tone.

February 11, 2002

To anyone who cares to read it . . .

I am 54 years old and for some reason feel like writing my feelings down for posterity.

I am not sure if anyone will ever read this, but it’s somehow cleansing to express my thoughts . . .

He gasped. Did she know she was going to die early? She pleaded to be remembered. She doubted anyone would care. She needed a proof. Like a stab, his heart bled reading it.

. . . now involved in grandparent stage. It happened so fast, so many memories I’d like to hold on to. I hope I hold on to them as they seem to be fading.

Her style grew more contemplative, more formal, as if she was staring eternity in the face, giving her last account.

March 2006

As I approach 59, I worry about the road ahead and pray it will be a smooth and easy one and not filled with bumps. I pray that Nathan and I will continue to enjoy it together . . .

He sighed with relief, as if she smiled to him after a long, exhausting trip nowhere and back, telling him, “Don’t worry, we will come out of it all right.” She did have a hope for them. In her thoughts, they were still one. For a fleeting moment, he felt less alone.

And then she was bidding farewell to her things.

August 5, 2007

My so-called office is full of memories and keepsakes and I hope someone will go through everything before the Dumpster comes. Daddy (Nathan) has threatened me with this threat many times . . .

How could he have done that, threaten her to take all her cherished time capsules away? But he did. Recklessly, he thought they were going to live forever, and there will always be time to take back words. Now they were hanging in the air, like a tightrope across an abyss, and he had to walk it. Was she still feeling the threat, wherever she was, or she could see him now, his eyes red, reading these words of a dying woman, his wife of so many years, holding on to the little that’s left of her life?

. . . and that’s that. The sum total of a person’s worldly goods can fit on one-half a page. I’ve enjoyed everything to its fullest, and I’m grateful to God for all the goodness I received.

He was crying. At last. He wished Vivian could see him, that she would know that he cried for her, with her, because it’s never too late.

August 15 2013

CAT scan confirmed. . . . Ovarian cancer.

Told kids that I had good life—the past 66 years have been sensational. Not too many people blessed with what I have—a good marriage, loving husband . . .

The tears were running freely down his face. Ever since she died Nathan has been desperately searching for these words. Even as her body was descending into the grave, he tormented himself with a question: “At the end, was she glad she said ‘yes’ to me back then? Did she know I loved her?”

Now he knew. Yes, she did, she did. Vivian said it. I am so grateful she was writing these diaries to tell me things I couldn’t hear. . . .

. . . a good marriage, loving husband who made life interesting.

Vivian at her best. Having learned about her impending death, she sat down to write an ode to life, a cascading, almost epic account of blessings she had.

Wonderful, bright, caring, religious children, who have merited special spouses and of course the crème de la crème my 30 fabulous grandchildren. I did lots of traveling, have 3 beautiful houses, no dearth of jewelry, clothing, silver, and anything I might need. My husband made me proud—he is very caring and generous with his time and money.

Nobody has everything, I always told my kids. Always look at what you do have, not what you don’t have. Count your blessings and be thankful always. I kinda thought that since I lost my beloved mother young and had a heart attack and diabetes, maybe I would sail through without any other problems. But it was not meant to be. Whatever happens.

As Nathan says, it’s been a great run.

It came from nowhere. Like a sudden broadside across the face, when everything gets crisscrossed in a double vision. She gave a title to her life, with his words. A great run. Were these her words, too, or she succumbed to his ambition, even to his vocabulary, to live a life he wanted?

He didn’t know the answer. It was new to him. Her diary was new to him. He realized that he never heard her really. Only now she spoke up.

“A great run,” she said, quoting him.

Even now, she remembers better.

He felt his throat burn. Something didn’t add up.

A great run, really? Was it all that mattered? Was it all he did, run?

Another layer peeled off.

He could almost see her. She was a spectator on the sidelines. He put her there, and she stayed there, always so faithful, clapping hands, happy for him, always. She was admiring him as he was sprinting off the start line. His trajectory, his speed, his endurance. But was she running? And now . . . his heart ached. No, she wasn’t running anymore, and it’s final.

Nathan could still remember that day so long ago, when the children were still little. Vivian played a game with them. She lined them up and asked them to choose a career. “But we need one doctor,” she said. “For our own insurance.”

“I’ll be the doctor,” David, the youngest, volunteered. He became an oncologist, Vivian’s oncologist, and she cashed in on the insurance she’d never wanted to need.

. . .

When she was diagnosed, Nathan immediately cut down on his work. Now it was all about Vivian. Spending days with her, bringing her to appointments, watching her carry the diagnosis without complaint, and something came back to life between them. A spark. An Indian summer . . .

Their youthful love blossomed. Now he remembered why he fell in love with her in the first place. Vivian cried. “It’s almost worth it,” she said.

August 2013, Day One of Chemo

I am realizing this is going to be a fight, a difficult fight I might not win. My fear is that someone else will fill my place. . . . I will become a faint pleasant memory, soon forgotten altogether. No one can live forever. Life moves on. I hope I have made my mark on my children. . . .

Nathan heard it loud and clear. Vivian, his Aviva who he loved back again, was not afraid of death. She was afraid of being forgotten, again. She felt forgotten for too long to be sure.

January 2014

I feel so much gratefulness to God, I have to express it to my family. I’m so thankful to be alive and all and enjoying the beautiful sunshine and clean air . . .

December 31, 2014

More chemo, more scans, more side effects . . .

February 11 2015

Liver biopsy very painful . . . .port insertion, and for 10 days couldn’t move my neck. . . . My tongue and mouth developed sores. Next came the rashes . . . extremely painful. How do I stay calm and focused with all happening to my body? I take out my iPad and look at all the beautiful pictures. The grandchildren are what keeps me going. . . .

Three days before she passed away, her children were sitting next to her bed. She always encouraged their talents. When her boys formed a band and released four albums together, she was the proudest mom on planet Earth.

Now she was in acute agony, in and out of lucidity. Her body was fighting its last battle. With great effort, she willed herself to come back.

“Sing please,” she said. They did, and she joined in, and the song took a life of its own. The doctor who came to check on her, stood at the door, in tears. He witnessed a sacred moment of a spirit that dared the death that refused to be defeated even as it was departing. A spirit that claimed its immortality.

Her life ended in a crescendo. During shiva, hundreds of people poured through the door sharing her story, how generously she touched their lives. As a virtuoso conductor, she bowed out, and the entire concert hall rose to their feet with rousing applause, and Nathan stood behind the curtains, for the first time ever, backstage, attesting to her greatness, to the courage of her soul to live the life to the very end.

He remembered those days as if it were yesterday. He remembered the singing. He knew, the children were singing for her, because of her. And all he could feel was a blessing of her descending light casting the last ray on him. He was basking in the radiance of her last moments of grace.

. . .

And then came that conversation.

“Remarry,” she told him. “I want you to. But promise me one thing. That I won’t be forgotten.”

Remembering, again. Could it be that he was always forgetting because remembering was too close, too real, whereas running after the next thing gave him an illusion of escape, of living for the next moment, never for the moment that was right there, right then? Or maybe he did learn something, something from her? And did she learn something from him?

He looked for an answer from Vivian. She was answering him, in her quiet, humorous, unpretentious voice that only a woman confident in herself would have.

I often marvel at the nice way he treats those many people seeking to relieve him of as much of his funds as they can. I do not always fare as well. Some select people I give to generously, but the many that ring my bell on a daily basis I admit to not being so benevolent.

. . .

And here is this voice again, talking about them, a couple of people coming of age, coming close to one another. At last, he was learning, reluctantly, but he was there.

My macho husband is really quite an emotional mush. As we age, things are seen in an ever-changing perspective. We’ve developed a closeness I feel that is somewhat enhanced by our being alone in this big house. Shabbat alone, I have come to relish for its simplicity.

He felt relief, as if an invisible hand that squeezed his chest, released its grip. So, at the end I wasn’t too foolish to lose her. But then the fear crept in again. Maybe it was just her, as always, forgiving, accepting, waiting . . .

Then he found this. Like a revelation, a writ of pardon, all the good that she saw in him, after all those years. And she said she wanted him there!

It is 1:30 in the morning and I hope I am tired enough to fall asleep now. I can’t wait for Nathan’s return. I need him to be home. He has always made life interesting. He is always ready to take on new challenges. People are always seeking his advice and he garners respect wherever he goes, and as soon as he opens his mouth. He goes an extra mile for a friend. He has wisdom and insight and has been my guiding light throughout our lives together. He is also ready to go places and is not daunted by traveling. So if things could just stay the same, the way they are now, I would be most grateful and appreciative. I am already almost 58. My first date with Nathan was on my 17th birthday!

I’m your guiding light? Vivian, your kindness, even now, is killing me, he thought, tears running down his cheeks. He was speaking to her now, to that invisible presence speaking to him from the pages, to that calm voice that had been the soundtrack of his life, the voice that came now to resuscitate him from emotional cardiac arrest. “I hope you’re right, Vivian, at least to some extent. It’s my last hope, that I was able to be for you who I promised I would be.”

The funeral was on the grounds of school where they first met and where he proposed to her and she said yes to him, and where they got married under the aerial support of Illinois-bound four-engine airliners. Now they were hovering high above, noise reduction compliant. Now she could hear him.

“Aviva,” Nathan said, his voice breaking. “Here it began, and here it ended.”

But maybe it didn’t really end, he was thinking now, because it never does. Maybe he can make sure her pledge was heard, and she won’t be forgotten. He will share her story, his story, their story. A story so public, so spectacular, and at the same time so untold where it needed the words the most, between them. And he can hope that somewhere someone reading this will say the words he feared so much.

I love you.

And maybe they will write a letter, before it’s too late. And they will play tennis for the sheer joy of the game, not the final win. And they will see the pictures together, not fearing who they became but relishing who they were and ultimately are.

This was her final entry. She wrote about joy.

The promise of new voices and excitement about their new beginnings is the thread that keeps weaving and creating new stories. The leaves that fell are being replaced, and spring is just on the Horizon.

Vivian, Aviva. You taught me to remember.

I will remember you.

1 Comment

[…] Reading Vivian […]