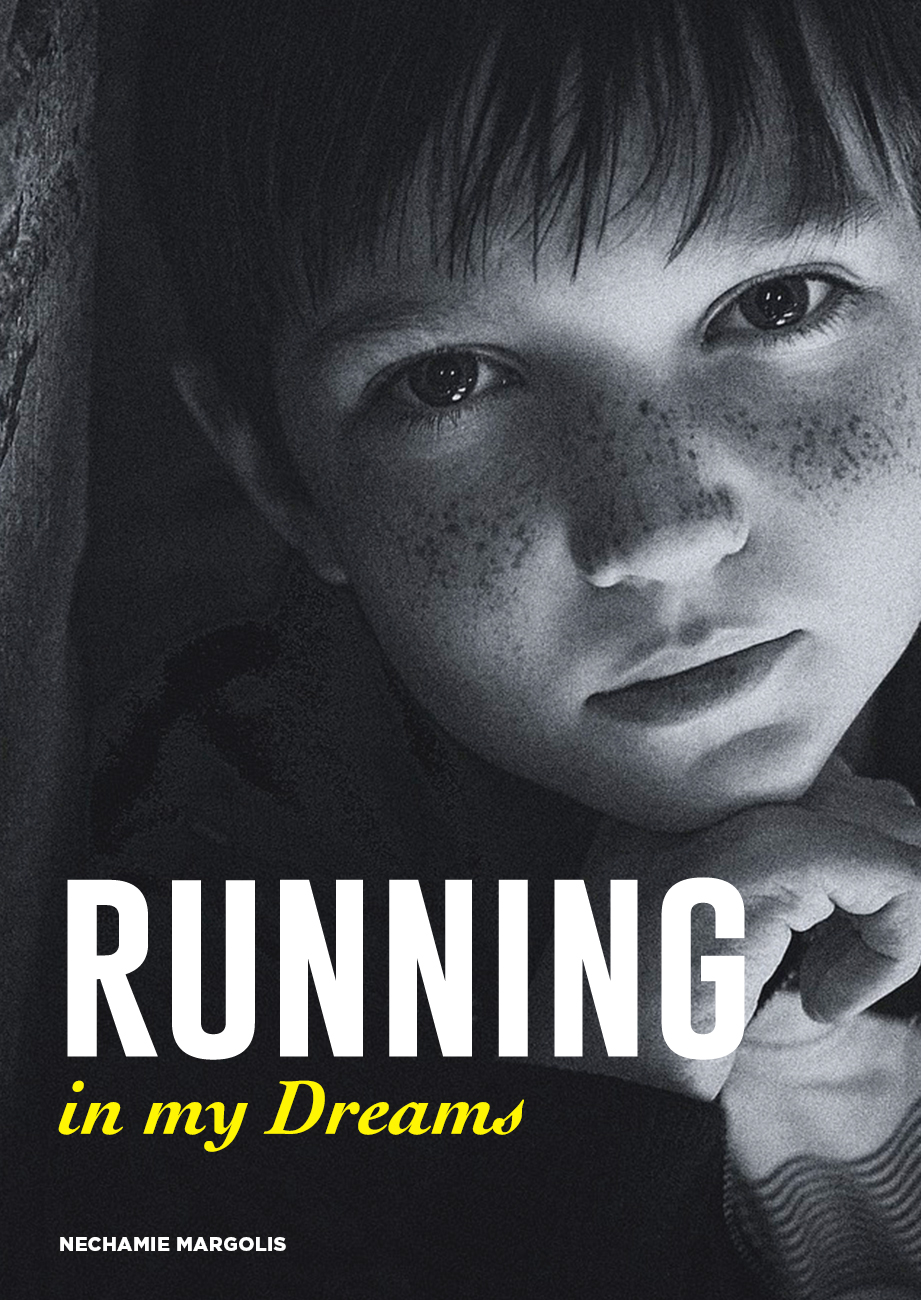

A young boy who has been diagnosed with a genetic illness teaches others what it truly means to live.

Running in my Dreams

From Shadow to Light

March 2, 2016

Welcome

October 27, 2016

Chapter One

December 25, 1999

Debbie’s desk looked like a little islet of light in the deserted open office space in the real estate management company where she worked. The entire place drowned in the twilight of late December. Everyone left early to celebrate. The secretary and a few other staff were wrapping up the last tasks before heading off for a long weekend.

Debbie also had to finish up a few things. Outside, early evening glowed with decorations, strings of colorful lights hanging everywhere. Frosty wind struck the windows with gusts of chilling fervor, which made the office feel even more empty. Just a final edit of these documents and a few faxes that have to go out, and I’ll be out of here, Debbie thought.

The phone rang.

The company policy had a rule against personal calls, and only a select few knew the emergency number to the main office. Otherwise, you never heard the phone ring. Hearing it ring on this particular evening meant only one thing; it had to be really important.

The secretary peered out of the main office and waved to Debbie. The icy gust from outside seemed to chill her bones. A phone call was bad news.

“Good evening,” she said, suppressing the tremor in her voice, making sure not to disclose the rush of anxiety suddenly squeezing her throat.

“Good evening,” a steady male voice reached her from the other end. “Dr. Roger Kula here.”

She gripped the phone a notch harder. Uri’s neurologist. A rock of a man, kind of a teddy bear but a strong one. He always spoke in a quiet, understated way. If he made the choice to call her on this evening, it must have been the news she needed to hear. Calling her at the office meant news that couldn’t wait.

“I have the results of Uri’s test,” he said. Paused for a moment. “It’s as we suspected. Duchenne muscular dystrophy.”

Debbie remained still. There was nothing for her to say, the news crashing down on her like a volcano eruption. She and her husband Moshe lived in fear for quite a while now, but still held out hope. Dr. Kula, the kindest man on earth, with his few words right now killed it. Debbie looked around. The room didn’t look the same anymore. It never would.

“Meet me in the office after the holidays,” Dr. Kula said. “We’ll talk more then.”

Debbie’s voice was raspy. “Is there anything we should do in the meantime?”

“Take pictures.”

“Pictures?”

His voice was coming as if from a great distance. Is he speaking to me from Alaska? Or maybe he is whispering so that the words won’t pound me too hard, she thought.

“There is a medication we can try. But your son may never look the same again. Take pictures.”

The pictures were in Debbie’s purse as she and Moshe drove to Long Island College Hospital to Dr. Kula’s office. She gingerly touched them but didn’t have the courage to take them out and give another look. In all of them it was her Uri as she knew him. An adorable three year old, almost four, with a heap of blond hair, and huge inimitable ever present smile.

Smile of a child who doesn’t know anything about the pain lurking behind the corner, she thought. And then another thought, barely registered in her mind, how long can we keep his smile alive? If only these pictures could keep the world at bay, not let it run off into that horrible fathomless black hole of Duchenne.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy, a terrible name that she learned to fear, made her shiver, fateful words replaying in her head on an endless loop. “Duchenne… spontaneous mutation…no treatment.” It’s about our Uri. He has it. This simple thought struck her like lightning, again.

Stacked together with the pictures was a huge sheaf of printouts. All the websites with information she’d laboriously researched about muscular dystrophy. Some of them seemed to be more credible, some less. But how will she know? Moshe, studious and systematic as only a banker knows to be, pored through every medical journal he could lay his hands on. They compared notes and pulled together all the information they thought relevant. If only knowing the inevitable could protect us from it, she thought.

The drive from their tree lined street in Flatbush to the sprawling complex of large drab brown buildings of the Long Island College Hospital was not long, but it felt like they went to eternity and back. Every street light was frozen on red, every turn was too slow to take in a dirty grey slush. Treading their way toward the building. Old clanky elevators, going and going and tugging along until Debbie lost a sense of direction. Why do they take so long? Are we going up or down, or maybe they go in concentric circles, spinning forever in a time warp?

At last the elevator leaped at the right floor, stood still for a few moments and noisily flung the doors open, letting them out. They walked down the corridor and entered the office.

“Have a seat,” the secretary motioned to a row of smooth molded plastic chairs that accentuated the feeling of getting lost in a dystopic world where humans, these biological organisms with blood and nerve endings and feelings like being unique, scared and in love, will be subservient to higher intelligence, statistical, cold, brutally efficient.

Debbie looked at Moshe. During the last two years he changed a lot. A reserved, soft spoken man, he had thick brown hair that dipped over his forehead, resting above his rimless glasses. His calm, steady eyes disclosed brilliance. My pillar, she thought.

For their entire marriage she was a blizzard of emotion. Her opposite, he was very cerebral, balanced, strong headed. He had a huge heart, but he was ruled by reason. A wave breaker that shields everyone from storms and high seas. And usually he had quite a presence to be reckoned with. As a vice president of a bank, he wasn’t used to sitting in waiting rooms. People waited for him. But now he didn’t even flinch. During the last two years he got used to being the suitor, to keep waiting, to hang on, hoping for the impossible.

His eyes rested on the plant in the corner. In this windowless nondescript waiting room it looked suspiciously lush and green. He resisted the urge to touch it to check if it was real. Must be fake, he concluded. How could a plant flourish in a room suffocating with anxiety, fear and desperation, and not even a single window?

But maybe, who knows, maybe it’s real. Maybe it lives, against all odds, same as his Uri will, despite a diagnosis, which is more like a death row than a medical condition. No doctor can take away his hope that his only son is going to have a miracle.

“Moshe and Debbie?”

They stood up.

“This way please.”

Dr. Kula greeted them at his desk. Uri’s medical file lay in front of him. A thick folio, full of blood tests, genetic testing and the final conclusive biopsy.

Dr. Roger Kula was not young. Full shock of white hair neatly combed to the left, big round smooth face. Having graduated John Hopkins in 1970, he practiced neurosurgery for a few decades, specializing in pediatric neuromuscular medicine. He was the guru of the neuromuscular. But he was also an exceptionally caring and kind man. His heart belonged to his patients, and they instantly knew it. As Moshe and Debbie walked in, he peered at them through his wire rimmed large glasses, eyes crinkling at the corners as he smiled in welcome.

Today, this kind man was going to tell them terrible things that they hoped so much to never hear. But he was going to say it kindly. As they came to learn during the past two years, more often than not brevity and radical honesty is the kindest thing.

“I won’t beat around the bush,” he said. “I’m not going to sugar coat the diagnosis, and give you hope where there isn’t.”

He opened Uri’s folder.

“Duchenne is a degenerative disease. It’s the most common fatal childhood disorder, which affects mostly boys, approximately 1 out of every 3,500 boys each year worldwide.”

Moshe and Debbie nodded. They knew that.

“Fatal means that there is no cure,” he continued, opening for them the door to a dark, long twisted road filled with ups and downs. “When the body functions normally, it produces a protein called dystrophin. This protein helps the muscle cells keep their shape and strength. Without the ability to replenish the dystrophin, the muscle cells gradually break down, which causes the muscles to degenerate, and a person gradually loses their ability to walk, and then sit.”

He looked at them. “I believe in laying out everything, as it is, so you can prepare,” he said. “Do you want to hear more?”

“Yes.” They wanted to know everything. They had to.

“Usually by the age of ten or twelve, a boy with DMD will need a wheelchair. His heart may also be affected and he’ll need to be closely monitored by a lung and heart specialist. Often they develop scoliosis. Their spine will get twisted and joints will stiffen. Then the muscles that control breathing are usually affected, and eventually they may need a ventilator–a machine that will help them breathe.”

“How fast?” Moshe asked. “How fast does it progress?”

“Every case is different.” Dr. Kula was unwavering. His calm demeanor helped Moshe and Debbie to hold their ground. He carried on. “Unfortunately, Uri’s case is already very advanced.”

“And the medication you spoke of?” Debbie said. “Can that help?”

“Steroids,” he said briskly. “Quite big doses of Prednisone. I have to make it clear. It’s not a cure. It may delay the progression of the disease, but it won’t stop it. And you must know the side effects.”

There were many. Weight gain and bloating. Stunted growth, acne, cataracts.

“We’ll take the prescription,” Debbie said firmly. “We will try whatever we can.”

The meeting took forever. Questions asked and asked again. Dr. Kula gave them all the time they needed. Their world was crashing down. They entered into a new scary world, and they didn’t know the rules. He had to be there with them.

And then Moshe asked one final time, knowing the answer but needing to know that he asked.

“Is there anything, anything we can do?”

Dr. Kula looked at them for a long moment. He saw they were exhausted, and they couldn’t hear again and again there was nothing to do. They had to do something.

“Take him home,” he said. Leaned forward, elbows planted firmly on the crowded desk, fingers crossed. His eyes, steady, compassionate, looked them both straight in the eye. This veteran neurosurgeon, a kind man who had seen so much, was giving them the best medical advice he had for them.

“Take him home and love him.”